Content

- A Historical Perspective on DAOs

- DAO in Present Times

- Hybrid Governance

- DAO Theatre

- Full DAOs and Pure Utility Tokens

- Full DAOs and Static Product

- Guidelines for Optimal Governance

- Centralised Entity That Integrates a DAO

- DAO Voting Panel

- Voting Power Mechanics

- Legislative Path Documentation and Design

- Voting Majorities Documentation and Design

- Opt-in Mechanics for Being DAO Member

- Minimal Threshold to Unlock Option of Being DAO Member

- Active Voter Bonus and Inactivity Penalty

- Ombudsman

- Tolerance Thresholds

- Delegation of Voting Power

- Legislative Initiative

- Miscellaneous Considerations

- Anti-Spam Measures

- Timeframe and Deadlines

- Conclusion

- Contact Us

- About Zerocap

- DISCLAIMER

- FAQs

- What is the historical perspective on DAOs?

- What are the limitations of DAOs in present times?

- What is a Hybrid Governance model?

- What is DAO Theatre?

- What are Full DAOs and Pure Utility Tokens?

31 Mar, 23

DAOs and Governance: Managing Tokenised Product Development

- A Historical Perspective on DAOs

- DAO in Present Times

- Hybrid Governance

- DAO Theatre

- Full DAOs and Pure Utility Tokens

- Full DAOs and Static Product

- Guidelines for Optimal Governance

- Centralised Entity That Integrates a DAO

- DAO Voting Panel

- Voting Power Mechanics

- Legislative Path Documentation and Design

- Voting Majorities Documentation and Design

- Opt-in Mechanics for Being DAO Member

- Minimal Threshold to Unlock Option of Being DAO Member

- Active Voter Bonus and Inactivity Penalty

- Ombudsman

- Tolerance Thresholds

- Delegation of Voting Power

- Legislative Initiative

- Miscellaneous Considerations

- Anti-Spam Measures

- Timeframe and Deadlines

- Conclusion

- Contact Us

- About Zerocap

- DISCLAIMER

- FAQs

- What is the historical perspective on DAOs?

- What are the limitations of DAOs in present times?

- What is a Hybrid Governance model?

- What is DAO Theatre?

- What are Full DAOs and Pure Utility Tokens?

A Historical Perspective on DAOs

There are many ways to manage a blockchain-based product and despite the fact that ‘DAO’ (Decentralised Anonymous Organisation’) is commonly recognised as a ‘must-have’ organisational setup of the token, it is neither the only way nor the best way. Among many possible ways of managing products on a day-to-day basis, doing that in a decentralised and fully anonymous manner is arguably the least efficient approach and risk-free approach.

The origins of DAO are rooted in the very idea of how blockchain functions. Nodes are validating on-chain transactions by converting them to so-called ‘hashes and consolidating them together as one big ‘hash chain’. Since the whole history of blockchain transactions and user wallets’ balances (as well as all other crucial metrics) are part of that hash-chain, it cannot be stored on a single server or controlled by one owner, without the risk of exploits, attacks or hacks. In order for the whole concept of the blockchain to work, it must become ‘immutable’ – that is impossible to alter or modify by malicious actors, and this can only be done by validating transactions and storing historical data by multiple various, independent actors not knowing each other’s identity.

To give a better context, most of the blockchains built in 2015 were ‘co-owned’, which means the whole blockchain transactions & wallet creation history has been continuously replicated across multiple servers owned by independent people. Anyone could become a ‘node provider’ as the only requirement was to own a given, predefined amount of ‘governance’ tokens and lock them in as a deposit.

Apart from acting as ‘archives of data’, most blockchain models have been relying on randomly selected node providers to ‘validate’ transactions. Using a hypothetical example, if you would want to transfer a given amount of tokens from wallet A to wallet B, this would result in performing interaction with the blockchain and adding an additional hash to it. This ‘modification’ could be permanently added to the blockchain (i.e. actually bring it into existence) if [n-amount] neutral, randomly selected, independent node providers would validate that transaction (i.e. confirm it is mathematically valid from a blockchain hash continuity perspective). Thanks to such validation, blockchain infrastructure can automatically reject any malicious or erroneous transactions.

It might be a bit hard to understand the ‘validation’ concept, but in truth, its main purpose is to avoid malicious actors like hackers or nodes acting against the network and trying to ‘rewrite’ the blockchain by artificially adding or removing tokens from wallets, simply by changing the wallet’s balance.

The above model was the perfect fit for DAO; validators could anonymously vote on adjusting key network parameters, and the result of the voting is the automatic execution via proper smart contracts. If any node provider has been red-flagged by the network as a ‘malicious’ actor’, tokens they have locked in previously as a deposit were simply ‘confiscated’ through the process called ‘slashing’ and redistributing to other holders.

The only ‘minor’ problem resulting from such a form of product management was a painful slowness in any blockchain upgrades and later development, which directly led to a massive spike in ‘alternatives’. Each alternative network has almost always been driven by the same business case: ‘we offer the same utility but we have upgraded something’.

While there is nothing negative in competition, as for now we have over 45 relevant blockchains, each and everyone promising to be ‘the best’ and ‘ultimate solution’. Such a high amount of separate economical and technical environments leads to the fragmentation of capital and progressively decreasing quality of products available in the DeFi (decentralised finance) sphere.

Decentralised applications (DApps) and web-based platforms offering utilities based on digital tokens and on-chain infrastructure are now replicated on each major chain. Instead of consolidating funds, know-how and user focus on one product, we now have duplicates of the same solution ‘but on a different chain’. There are hundreds of decentralised exchanges (DEXs), lending protocols, NFT platforms and metaverses, and each new one ‘steals’ a bit of user base and capital from existing competitors.

Notably, the worst part is that new products coming to space are – most of the time – not even the real products, but rather a set of documents with a very ambitious roadmap and high capital-raise expectations. In the best case scenario, the product is deployed as ‘MVP’ (minimal viable product) to prove the concept and utility for future token holders, but such an approach is still very rare, and even if MVP is actually delivered, it is often nothing more but a ‘fork’ (copy-paste combined with minor upgrades) of a competitor’s product.

The aspect of IP protection, or an absence thereof, is where decentralised models have shown their biggest disadvantage – since smart contracts are publicly available anyone can simply copy and re-use them in different products. With no central point of responsibility, there is no one capable of executing basic IP protection rights.

Lack of central authority also means that external traders and investors are free to manipulate the price of the tokens on a secondary market through intentional ‘pump & dump’ exploits that are impossible to prevent without authority being able to detect and blacklist involved wallets. This category of exploits was particularly visible and devastating during token generation event (TGE) events where the price of the tokens was raised dramatically by bots buying off large portions of early liquidity and then dumping it to harvest the profit.

Finally, DAO-managed projects have opened a door for all sorts of capital exploits by the ‘team behind the project’ itself. Whether it’s hacking treasury wallets by the team members themselves and telling the world it was an ‘unfortunate event’ or simply dropping the development of a promised product mid-way after harvesting early profit (this is referred to as a ‘rug-pull’). For many products lack of identity correlates directly with a lack of responsibility, which has proven too tempting for many anonymous individuals.

Ultimately, as you can see, blockchain evolution history (from 2015) can be presented as a specific form of a ‘chain reaction’. In this chain reaction, DAO’s inability to improve the base blockchain infrastructure in a dynamic, iterative and effective manner has led to the creation of more chains. These chains have hundreds of duplicate dApps and token-based business models. This, in turn, results in decreasing quality of the decentralised industry in general.

DAO in Present Times

As of now DAO governance model is promoted as a unique way of ‘democratic’ co-management and co-governance over a blockchain-based product. Unfortunately, this is pure fiction. On the bright side, however, more and more people are becoming aware of this.

The reason why DAO can never be used as a democratic tool lies in the very concept of tokenisation itself. If the right to vote is based on owning the tokens, and vote ‘power’ is calculated based on the number of tokens held, anyone can either accumulate a majority of tokens in circulation and change the democratic model to centrally managed (referred to as ‘whale monopoly’ or ‘whale domination’). Limiting the number of tokens or votes per wallet is not a solution, as someone can simply set up multiple wallets with a combined majority vote (which is called ‘sybil attack’ or ‘multi-wallet exploit’).

To prevent the above from happening, most of the time, the majority vote is anonymously tied back to the original managing team, so that it could retain control over the product and effectively run its further adoption and expansion without risking interference from DAO members. From a product management perspective, this approach could be considered a ‘lesser evil’ compared to allowing whales to gain a dominant position in DAO and risking that they would vote against the product (for example, preventing crucial upgrades).

Nonetheless, when products become a bit more complicated than a set of few features, the risk of DAO voting on potentially dangerous and counter-affecting ideas increases dramatically. Hence there is a need to control and filter out ideas or suggestions submitted for voting in the first place. As a consequence – there is always a need to form some ‘central’ committee, responsible for reviewing and accepting voting submissions. Central committees or other forms of review panels are the points at which most DAO democracies end. If that committee would have been selected in a decentralised, democratic manner – looking at previous considerations – it would be still either composed of whale-appointed individuals or managing team members.

All in all, deciding on DAO-managed product development nowadays comes down to choosing between a dangerous and potentially self-destructing, truly democratic model or a fiction of democracy in which both executive and legislative parts of the managerial structure are actually centralised backstage.

Hybrid Governance

Keeping a DAOs organisational structure agile is the only way it can keep adapting to industry changes as well as be able to collect and implement improvements based on iterative feedback loops. Achieving the above simply cannot be done through the model introducing a need to vote for any change in the first place. Even if later execution is managed by a dedicated centralised unit, it’s still inefficient.

Apart from the above, introducing a DAO will almost inevitably end up either in whales taking over the majority of voting shares or managing teams retaining control through seemingly neutral, anonymous wallets. From a legal standpoint, the fictional democratic model (often referred to as ‘DAO theatre’) triggers an entire wave of potential risks and legal consequences (described in a later section).

From an organisational perspective, one of the best and most honest approaches to be adopted is referred to as the ‘hybrid governance model’, which retains some of the old ‘DAO’ model features and combines them with a transparent, centralised execution committee, built from both management team and chosen community members. Such a model effectively covers 3 basic needs for tokenized product management which are:

- Existence of executive body

- Existence of legislative body

- Existence of jurisdiction

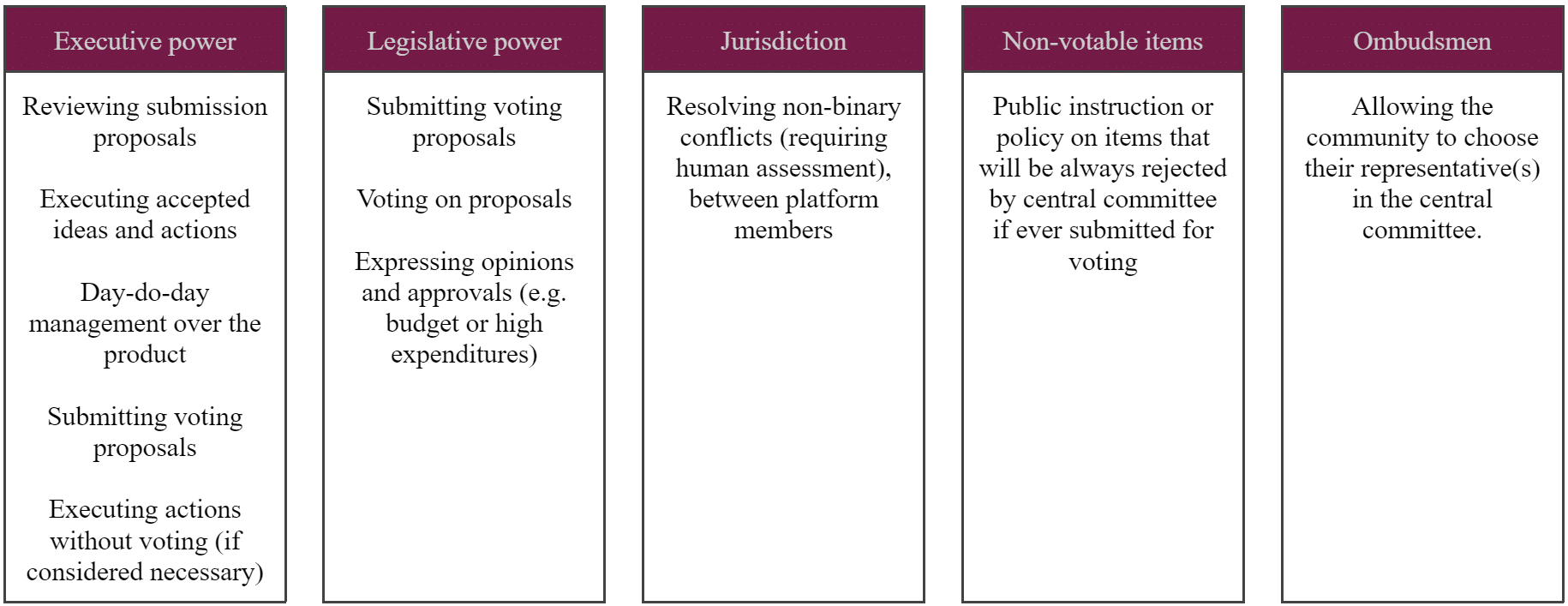

Above division of responsibilities and prerogatives is not novel – it was proposed back in the 18th century as a ‘separation of powers’ by Montesquieu and adopted by most of the modern countries later on. This concept can be visualised in DeFi and is expressed below:

Central committee is responsible for the ongoing, day-to-day management of the product. It is not chosen by the DAO (as this would introduce unnecessary fiction of democracy) but is transparently presented as a body composed of central management team members. Optionally, DAOs can appoint one or several community members to the central committee. They can be observant, challengers, advisors or even have voting rights, but they should never have the possibility to form a majority. Appointed committee candidates should also be asked to reveal and confirm their identity before becoming formal members; this might be achieved through background checks or requesting candidates satisfy Know Your Customer (KYC) requirements.

Apart from setting up one central committee, it’s viable to consider the creation of additional sub-committees, with dedicated tasks allocated to them. For example:

- Technical committee – responsible for reviewing and pre-screening ideas related to technical product infrastructure and setup.

- Business committee – responsible for the day-to-day management of the administrative back-end, relations, brand building, product development, client reach and more.

- Fiscal committee – responsible for token economy design and monitoring key market metrics related to the token. This committee also has the authority to make decisions related to the redistribution of tokens, rewards, buybacks, mining and burning.

One of the most important roles of the executive body is to review and approve voting proposals before they are voted on by DAO. Most times, the review focuses on checking whether or not the submitted item is not soliciting the ‘non-votable items’ policy, i.e. suggesting change or introduction of a solution the area that is considered a foundational aspect of the ecosystem, and should not be changed, for example:

- Anything related to fiscal policy (such as a motion to change supply, to mint tokens, to burn tokens, to distribute airdrops or rewards, making specific expenses, purchases and more).

- Matters related to external partnerships policy (this includes motions to enter into partnership with specific blockchain, motions to list tokens on a given exchange, motions to create specific liquidity pools and more).

- Foundations of a governance model and business profile (for example motions to change/reorganisation governance model, motions to change the core business profile of the product and more).

- Other motions that could be interpreted as interfering with the core, foundational setup of the product and its organisational or infrastructural backend.

The hybrid model recognises DAOs as both a legislative and jurisdictional body.

As a legislative body, the DAO’s role is to vote on all of the submitted ideas, propositions and changes to the product – after their approval by the central committee or a dedicated committee. With its jurisdiction, DAOs can effectively manage a decentralised form of resolving in-platform conflicts. The hybrid governance model shifts the DAO’s legislative role more towards focusing on improvement ideas, suggestions related to upgrades or modification of product features and possible functional expansions. Fundamentally, this model strengthens DAOs and emphasises their role as a ‘voice of users’.

Submitting ideas for improvements should be promoted and incentivised as much as possible. This can be done through improvement rewards; tokens or ‘points’ for top-voted ideas can be leveraged here, especially as retroactive rewards for those improvements which have been implemented. Feedback expressed by a DAO’s members is then reforged into living actions and plans by the central committee, making these two bodies act in great synergy.

One of the most important good practices DAOs can adopt is a routine of publishing yearly reports summarising activities performed by the committees throughout the year, their achievements and delivered features and products. Annual activity reports are further a great tool for building long-term trust with a DAO’s users and investors as well as an additional way to boost your credibility and transparency in the DeFi industry.

A central committee might subject the report to DAO ‘acceptance voting’ or even ask for the DAO’s opinion or approval on budgets and expenditure tolerance threshold for a given fiscal year or shorter period. Although the hybrid governance model does not equip legislative power with any tools that could actually enforce the central team to take the results of such votes into account, this latticework for coordination focuses on user feedback and assessing their confidence and support for future development and fiscal plans.

There are multiple ways in which hybrid governance models can be implemented. While detailed aspects and solutions are described in a separate section of this guide, please refer to the table below, summarising the foundations of that setup.

DAO Theatre

One of the most popular models of tokenized product management models that have been consistently adopted by the majority of projects over the last several years was the so-called ‘DAO-theatre’ model which always guarantees the DAO majority vote, albeit without ever publicly admitting it. Although this has proven a popular approach, being adopted by products that made a successful impressive capital raise, this paradigm is far from being effective or safe.

First of all, the DeFi community is getting more mature with each passing day. What was once something understandable by only a fraction of users and investors is now becoming a public, common point of knowledge. Introducing the DAO model was initially perceived by the majority of blockchain users as a must-have and good practice; however, after the unignorable number of events that displayed the severe inefficiency of the governance mechanism, this stereotype is wearing off. Presently, it is likely that if one is planning to establish a DAO and sell it under the euphemism of a democratic model, sooner or later someone from the organisation’s community will discover, document and publish a history of on-chain transactions that have secured the team’s or whale’s majority votes.

Looking from a different angle, supposed ‘anonymity’ is being branded as the biggest DAO advantage. Releasing it from legal obligations towards local regulators relating to issuing securities and stepping into the role of the financial institutions is virtually not achievable. Unless the creator of a DAO truly intends to make your token a pure utility and governance asset without raising any capital prior to releasing it.

No one is ever fully anonymous, apart from particular cases in which a token released has been preceded by seed, private and public sales in which one acted under their pseudonymous identity when signing off the deals. In most situations, a DAO’s product will always need an identifiable point of contact to manage it; an example of this is the backend infrastructure of these organisations – unless a DAO leverages decentralised cloud storage, its domains and servers are owned and paid from an identifiable account.

Finally, using a DAO as a legal buffer to avoid regulations that would have otherwise been applicable (and more often than not, limiting) will most likely backfire at some point in future. This is especially relevant considering that financial and banking regulations along with taxation related to DAO products and services are some of the most strict and enforceable jurisdiction branches.

Looking at many different regulations, assumptions can be made around the deliberate and conscious creation and distribution of a digital share unit; the direct or indirect intended purpose was to acquire monetary value in the future. As such, the digital share unit leveraged by DAOs has the capacity to be traded for other goods or assets; this form of trading is primarily catalysed by price speculation relating to the implied future value of that share unit. Notably, the ability for regulators to make new regulations effective retroactively, the DAO theatre model is not something that can and should be advised.

Full DAOs and Pure Utility Tokens

Considering the open source and permissionless nature of many blockchains, anyone can mint and distribute fungible tokens to a group of anonymous users, even if these tokens do not have any monetary value. Similarly, individuals can then easily use received tokens to create a liquidity pool with it and, as result, change it to a value-bearing asset. This loophole is sometimes used as a gateway to issue a token and distribute it as nothing more than a ‘tool’ and ‘voting unit’, without mentioning anything about its future possible price or value.

In real life, issuing on-chain assets as a pure means of utility and governance is counter-intuitive, achieving the same purpose would be far easier, cheaper and more comfortable for end users without the implementation of a blockchain-based infrastructure. Further, it is against any business logic to implement tokens as a part of a product’s utility and expect your users to bear the additional cost of interaction, and gas fees, anytime they want to use your product. This can be analogized to asking Facebook users to make a small micropayment anytime they want to put a like under some content.

The only logical, rational reason to buy and use such a token is the expectation that it will gain monetary value in future and will be possible to use as an earning tool or sold with profit. As a result, these pure utility and governance tokens edge closer towards the fringes of being a security. If a founder’s intentions or future visions are having the utility or governance token traded on decentralised and centralised exchanges, consideration should be given to transparently disclosing such a plan to their legal advisor in order to get an expert opinion explaining the consequences related to such intent.

Full DAOs and Static Product

As mentioned, the deployment of ready-to-use solutions using smart contracts and decentralised file storage structures can be accomplished in a fully anonymous manner, provided that the individual has not revealed their identity to third parties in order to enter into deals such as capital raise. If an individual deploys their product with a pure “utility and governance” token, this action can be considered legally compliant even if their identity remains unknown. However, releasing one-off, ready-to-use products with tokens being value-bearing assets could be viewed as an illegal circumvention of regulations related to financial institutions. Accordingly, taking this approach is strongly discouraged.

Regardless of the legal validity of the aforementioned approach, introducing one-off solutions with little or no level of upgradability has been proven to be non-efficient and non-sustainable in the long term, especially for products requiring a high degree of innovation and the introduction of an improvement-feedback loop. This issue has already been addressed at the beginning of this report, so it is sufficient to summarise this approach as malfunctioning, slow, and, in most cases, legally non-compliant.

Guidelines for Optimal Governance

So far, this report has covered high-level considerations related to various approaches to managing decentralised products and recommendations related to the most efficient, transparent and legally compliant variants. This section provides a detailed overview of specific hints, tips, guides and optimal solutions related to the governance setup. Each suggestion has been classified as either ‘critical’ or ‘optional’ depending on its importance and added value.

Centralised Entity That Integrates a DAO

Type: Critical

Description: Early-stage development is the most dynamic stage in the entire lifecycle of the product. If implemented too early, a DAO might be more of a burden and an obstacle to the project’s development rather than a benefit. The introduction of decentralised governance based on a hybrid approach recommended within this guide is certainly not a number one priority and can be postponed to later stages of the roadmap. The logical reason behind postponing DAO implementation is that one of the main features and added value of the governance panel is expressing and filtering user feedback, making DAO members one of the most effective beta testers that you can get. However, in the early stage of development, most of their suggestions and ideas would be either too early or duplicated with what you have planned in the first place.

DAO Voting Panel

Type: Critical

Description: When a project is preparing to deploy a DAO, one of the most important and obvious features is the voting panel. It is important that you keep this function as simple to use as possible. It would be optimal to make a ‘DAO’ button included in the user’s menu and link it with a personal DAO panel, in which the user can see the list of all upcoming votes as well as the one which has already ended, together with their results, documentation, attachments and central committee opinion. Voting panels should also reference users to all additional information, policies and rules related to voting; this includes explanations on how voting works, what voting majorities and legislation path, a list of non-votable items, voting power delegation and more. Developers might consider including additional links to step-by-step instructions on how to make a DAO voting proposal.

Voting Power Mechanics

Type: Critical

Description: It’s important to document and implement rules related to voting power. The most standard model requires users to stake their utility/governance tokens on a staking vault first, and in exchange, they receive so-called ‘voting power’ or ‘voting points’. There are different approaches as to how many voting points should be given to the stakers for their staking contribution, the most popular ones are:

- Amount of voting points is equal to the amount of staked tokens, or the number of tokens multiplied or divided by [n] number – this is the most balanced approach and makes no preference towards bigger or smaller stakers.

- Amount of voting points is equal to the amount of staking score (or some other loyalty punctuation mechanics); this approach pairs the number of voting points with the total score calculated based on a time-value weight of staked tokens – typically DAOs average one’s amount of tokens staked during last x months.

Upon implementing an advanced loyalty appreciation model, developers should consider allowing members to gain voting power only after a specific user level is gained, to limit the amount of people entitled to make governance proposals. Specific limits can be met either by a single wallet or a group of wallets using the voting points delegation feature. Moreover, it is important to understand that voting points are used to express the mathematical ‘strength’ of a single wallet’s vote – not as spendable, tradeable currency.

Legislative Path Documentation and Design

Type: Critical

Description: Users should have a clear understanding of what is the process after a proposal is submitted for further voting, what are possible outcomes and how to submit the idea in the first place. The following implementation and documentation of workflow are recommended:

- Users or groups of users submitting the proposal need to choose a relevant committee to review the submission.

- Note that if there is only one central committee this is not applicable.

- Committees might redirect the proposal to other committees if needed or invite that committee for joint review.

- Reviewing committee might accept or decline proposals

- In a multi-committee setup, rejection of the proposal can be subjected to an ‘appeal process’ and sending the proposal to re-review by the central committee (usually considered as a higher instance).

- A single committee model appeal process can still function effectively; this requires creating two instances of reviewers, the first can be composed of 3 selected team members and the second would be the entire managing team plus community representatives (ombudsmans).

- Importantly, in the case of small teams and single committee setup, an appeal institution makes less sense.

- If the proposal is rejected, it is still documented and stored in the ‘rejected’ archive.

- If the proposal is initially accepted, it is sent over for DAO voting.

- The DAO vote is automatically shared with the central committee. It’s important to note that the central committee, by default, is respecting the result of DAO voting but is not bound by it – this is one of the main differentiators of a hybrid governance model.

- Central committee is then responsible for executing the proposal (for example, through internal resources or by funding grants for external developers).

- It’s good practice to include a summary of how ideas and proposals accepted by the DAO have been executed or managed by the central committee in the yearly activity report, shared with the community.

Voting Majorities Documentation and Design

Type: Critical

Description: Each voting period should have a winning majority attached to it and documented. Depending on how one’s team is organised, you might adopt various voting mechanics or even remove internal voting altogether. As of the DAO, the most standard winning majority is a simple majority (more votes in favour than against), with no definitive quorum requirements. Depending on your preference, you might alter that model by modifying three variables:

Winning majority:

- Standard: More votes in favour than against

- Absolute: Amount of votes in favour is bigger than the amount of votes against by specific % or n

- Qualified: Amount of votes in favour is x% of all entitled votes

Quorum (amount of people who has participated in the voting, so the voting is valid):

- No quorum (most popular one)

- At least 50% of entitled wallets

- Full quorum (not recommended)

- Custom quorum

Opt-in Mechanics for Being DAO Member

Type: Optional

Description: It is generally recommended that builders should introduce participation in DAO as opt-in mechanics. It means that simply because someone has staked a sufficient amount of tokens to become entitled to vote does not mean automatic inclusion in the DAO – especially when inactivity penalisation is being introduced. Instead, it makes more sense to include the ‘Join the DAO’ button which gets unlocked when the user reaches a minimum level of the account.

Minimal Threshold to Unlock Option of Being DAO Member

Type: Critical

Description: As previously mentioned, it is recommended builders levy an entry threshold to become a DAO member. The amount of tokens unlocking DAO membership should constitute approximately 0.005 – 0.01% of the total token supply, however, this assumption needs to be verified by the initial valuation of that supply after the TGE event. From a capital-wise perspective, a rough rule is that users who stake $1000 – $2000 worth of tokens for approximately 6 to 12 months should qualify as an individual who can join the DAO.

Becoming DAO members means that users can effectively vote on every proposal, yet submitting one should be subjected to an elevated threshold of the voting power. For example, this might be that voting power or the ability to create a proposal is only received if 0.5% of the total token supply has been staked for 12 months.

Active Voter Bonus and Inactivity Penalty

Type: Optional

Description: Since the DAO is one of the most effective channels of expressing user feedback and opinion, it is correspondingly logical to introduce additional bonuses for active participation in voting and social arbitrage (if implemented). The ‘continuous activity’ bonus would mean that DAO members progressively unlock rewards multipliers (within the weighted rewards distribution model), per each n amount of votes and social arbitrages they have participated in an unbroken sequence. For example:

- 5 votings/arbitrages in a row: +2% voting power

- 10 votings/arbitrages in a row: +5% voting power

- 20 votings/arbitrages in a row: +10% voting power

Since a bonus is calculated based on ‘unbroken’ sequence of active participation, missing a single vote or failing to fulfil social arbitration duty would reset the sequence to zero and would require the user to start over. With respect to the penalisation of inactive DAO voters, it should be considered an optional measure and should not be pushed too far to avoid disincentivising from voting. The risk of losing the bonus described above should be considered a sufficient form of penalisation. In the case that losing additional benefits would be considered a weak form of inactivity penalisation, DAOs can establish temporary DAO membership bans (for example, 3 months) if the user is skipping more than n amount of votes in a row.

Ombudsman

Type: Optional

Description: The term ‘Ombudsman’ originates from the Swedish language and means ‘representative’. It is also commonly used in modern politics and related to public officials appointed by the government or parliament to be the ‘voice of the people’. Ombudsman usually has their own legislative power, which means they can submit voting proposals.

In the hybrid governance model, an ombudsman (a single one or a group of them) can be elected once a year by the DAO. The following logical rules related to that institution are recommended:

- Candidates should go through KYC and their identity should be publicly known and confirmed.

- Ombudsman can submit a predefined n amount of voting proposals directly from their account.

- Anyone can reach ombudsmans with a query, question or suggestion related to potential improvements.

- Ombudsman should be able to block or filter unwanted messages from the community to avoid spam

- A consideration here would be the implementation of a disincentivising mechanism, such as an ‘ombudsman query validation deposit’ – a small fee that is being returned back to the user if the query is not a spam or similar low-quality message, and otherwise confiscated.

- Ombudsmans should be also included in the central committee, they can have voting power as well (if applicable and viable), but they should never be able to take full control of the committee (e.g. sum of all ombudsman’s votes in a specific committee should always be a minority).

Tolerance Thresholds

Type: Optional

Description: Implementation of a tolerance threshold relies on the initial implementation of a specific threshold related to either budget or scope of involved matters that require approval from higher instances in governance structures. This can be implemented on two layers:

- A dedicated committee might be required to seek approval from the central committee for any budget expenses crossing pre-agreed threshold limits. This might include total monthly, total annual, average monthly, average annual, single expense max and more.

- A central committee might seek similar approval or opinion of the DAO on such a threshold as well. However, since the central committee is never legally bound by the DAO’s voting result anyway; hence, it is more frictionless to make votes in this category a matter of opinion rather than approval.

Delegation of Voting Power

Type: Critical

Description: Delegation of voting power is a very common solution allowing one user to delegate voting points to another wallet. This mechanics makes sense in the case that there are two governance staking thresholds being implemented (refer back to the ‘Minimal Threshold to Unlock Option of Being DAO Member’ item above), as it allows stakers with lower staking positions to combine their voting points and effectively submit proposals together. The following logical rules are optimal solutions for voting power delegation:

- Users can delegate only 100% of voting power – partial delegation is not allowed.

- Users who received delegated voting points can freely use them for voting without any additional approval from the delegating party.

- Users can withdraw voting points delegated to other users anytime with immediate results, however delegating points again (once they were withdrawn) can happen only if 24 has elapsed from the last withdrawal. This can be referred to as the ‘redelegation cooldown period’.

- Double delegation is not-allowed – users can’t delegate voting points that have been delegated to them from other wallets.

Legislative Initiative

Type: Critical

Description: In general, a legislative initiative in decentralised governance should equip a given person or body with the possibility to create and submit voting proposals without standard voting power requirements. Possible parties that can be equipped with such privilege are:

- Central committee

- Dedicated committees

- Ombudsman(s)

When it comes to dedicated committees (such as a fiscal committee or technical committee) and ombudsmans, there are two ways legislative initiative can work:

- Indirect – with central committee review

- Direct – without central committee review i.e. direct submission to DAO voting.

Quantitative limitations of proposals can be introduced that enables a central committee to submit per month or quarter. Finally, voting submissions submitted by parties equipped with legislative initiative can be either treated as a standard voting proposal (that is, added to the voting queue) or privileged (that is, voted immediately after submission).

Miscellaneous Considerations

Voting Queue

Important aspect of the hybrid governance model is defining how the voting queue will work, specifically relating to the order and priority in which proposals are to be voted on. There are two approaches that can be taken:

- FIFO (first in, first out): This is the most straightforward approach, however, if DAO has a limit of n proposals that can be voted on during a single epoch (perhaps 1 day or a custom number of hours). However, these mechanics can delay voting on important matters in the case of a high number of submissions which leads to a significant voting backlog.

- Upvote system: This is a more dynamic and recommended approach in which voting points are not only used as a mathematical weight of a single wallet vote but also as a means to ‘upvote’ certain ideas. In relation to the upvoting process, voting points can be used as a spendable currency, meaning that if a user has more than one point, he can freely distribute them as upvotes across any available pending voting proposals. In each voting epoch, the DAO votes on the top upvoted ideas.

- Upvote system & priority exception: This is a modified upvote system in which voting proposals submitted by privileged parties are voted immediately without a need to be upvoted. In the case that there are multiple voting proposals submitted by different privileged parties, the default hierarchy should be:

- Central committee

- Dedicated committee

- Ombudsman

And if there are more proposals submitted from the same party, by default, they are sequenced using FIFO rule. Ultimately, the central committee should be equipped with the possibility to rearrange the voting backlog manually; however, any interference in voting proposals made by the community should be done only if absolutely necessary. Accordingly, unnecessary confusion and irritation caused by unsuspected delays or preferential treatment can be avoided.

Anti-Spam Measures

One of the commonly reported issues or risks flagged before governance model implementation is spamming avoidance. In other words, it’s crucial to document and deploy measures that won’t allow users to abuse their right to express feedback and opinion. A particular risk that requires absolute remediation is the risk of overburdening the central committee (or other privileged parties) with too many voting proposals to be reviewed. It can be remediated by:

- Appointing a dedicated review group (for example, 2 team members and an Ombudsman)

- Separation of dedicated committees for selected types of submissions

- Setting up submission proposal limits

- For other privileged parties – specific quantitative n amount per week and month

- For DAOs members – specific quantitative n amount of proposals per specific q thresholds of combined voting power owned by the wallet per week and month:

- 50k voting power: 1 voting proposal per week

- 100k voting power: 2 voting proposal per week

- 250k voting power: 3 voting proposal

Specific thresholds of voting power that establish a submittable weekly amount of voting proposals, need to be carefully defined based on the method adopted to generate users’ voting points, so as they are reasonably correlated with specific % shares of total token supply.

Timeframe and Deadlines

The governance model of DAOs should document and define a set of rules related to the voting timeline, that is after what time voting is closed and all the votes are calculated to decide what the outcome is. We believe optimal voting timelines are:

- 72 hours to close the DAO voting (note that if the upvote system has been implemented, 72 hours would start to elapse once a specific voting item has been pulled on the voting agenda, consisting of a max amount of n items. This means that if the maximum size of the voting agenda is set as 5 proposals, the DAO’s processing capacity is 5 top upvoted proposals per 72 hours).

- 24 hours to review the proposal by the central committee or a specialised committee

- 24 hours to submit an appeal (if applicable) and a subsequent 24 hours to review the appeal (if applicable)

- First month of the organisational/fiscal year for the election of community representative(s)

It’s important to note that the following deadlines should be treated as instructive which means that even if they are crossed, it does not instantly mean that proposal is automatically rejected or approved:

- Preliminary review and subsequent approval or rejection of the proposal

- Post-appeal review

- Community representatives elections

Alternatively, lack of timely response from the committee could be treated as lack of approval and hence rejection, however, this is less user-friendly approach and as such, less recommended. Nonetheless, if a DAO decides to adopt the ‘silence means rejection’ approach, it is recommended that they consider extending the approval deadline to 2-5 days to avoid unintentional rejection of potentially viable propositions. On the other hand, deadlines predicted for the community should be considered as ‘material’ meaning that whenever they’re crossed, it means materialisation of the specific result (either closure of the voting or disabling appeal option).

Conclusion

Ultimately, DAOs offer a novel method of governance that has the potential to transform the way businesses operate and make choices. In order to realise their full potential while they are still in their infancy, it is crucial to carefully evaluate the ideal structure that will support an organisation’s objectives. Decentralisation requires striking a balance between autonomy, efficiency, and inclusion – evidently a difficult challenge. Creating strong governance structures requires overcoming these obstacles, which can be done by taking inspiration from already-existing models like the separation of powers.

With reference to properly architected DAOs, effective coordination and transparency are essential for promoting cooperation and confidence among stakeholders. DAOs can get beyond restrictions that have previously limited their usefulness by expanding on existing governance systems and combining components of transparency, accountability, and collaboration. Future governance frameworks may be more decentralised, encouraging transparency, and inclusive, attributable to this adaptable, modular framework.

Contact Us

In case you’re interested in purchasing one of our due diligence and consulting packages or would like to get more details on the above, feel free to reach us via [email protected] or [email protected]. You can also contact us directly through one of the following telegram IDs:

- @d_dum – QuantBlock’s CEO

- @nathanZC – Zerocap’s Innovation Lead

About Zerocap

Zerocap provides digital asset investment and digital asset custodial services to forward-thinking investors and institutions globally. For frictionless access to digital assets with industry-leading security, contact our team at [email protected] or visit our website www.zerocap.com

DISCLAIMER

This article, authored by QuantBlock, is published on Zerocap’s website for informational purposes only. The content, views, and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of QuantBlock and do not represent or reflect the views, opinions, or positions of Zerocap. The information provided should not be considered financial advice, and Zerocap bears no responsibility for any actions taken based on the article’s content.

Zerocap does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the information provided in the article. The industry sector discussed is subject to rapid changes, and the content should not be regarded as universally applicable or definitive.

For any concerns about the article’s authenticity, please contact QuantBlock directly at [email protected].

FAQs

What is the historical perspective on DAOs?

Decentralised Anonymous Organisations (DAOs) originated from the concept of how blockchain functions. Nodes validate on-chain transactions by converting them into ‘hashes’ and consolidating them into a ‘hash chain’. This process requires multiple independent actors to validate transactions and store historical data, making the blockchain ‘immutable’. DAOs were perfect for this model, with validators anonymously voting on adjusting key network parameters.

What are the limitations of DAOs in present times?

DAOs are often promoted as a democratic way of co-managing and co-governing a blockchain-based product. However, this is not entirely accurate. If voting rights are based on token ownership, it’s possible for someone to accumulate a majority of tokens and change the democratic model to a centrally managed one. This is referred to as ‘whale monopoly’ or ‘whale domination’.

What is a Hybrid Governance model?

The Hybrid Governance model combines features of the traditional DAO model with a transparent, centralised execution committee. This committee is composed of both management team members and chosen community members. The model effectively covers the existence of an executive body, a legislative body, and jurisdiction.

What is DAO Theatre?

DAO Theatre is a popular model of tokenized product management that guarantees the DAO majority vote without publicly admitting it. While this model has been widely adopted, it’s not necessarily effective or safe. The DeFi community is becoming more aware of the inefficiencies of this governance mechanism, and the stereotype of DAO as a must-have is wearing off.

What are Full DAOs and Pure Utility Tokens?

Full DAOs and Pure Utility Tokens are a way of issuing on-chain assets purely for utility and governance, without any monetary value. However, this approach is counter-intuitive and against business logic. The only logical reason to buy and use such a token is the expectation that it will gain monetary value in the future. As such, these tokens edge closer towards being a security.

Like this article? Share

Latest Insights

On-chain Bitcoin Metrics: The Main References

In the realm of cryptocurrency investment, on-chain Bitcoin metrics provide a critical lens through which investors can gauge market conditions and make informed decisions. These

What is the Base Blockchain? The Coinbase Layer 2

The Base blockchain, introduced by Coinbase, represents a significant development in the realm of cryptocurrency and blockchain technology. It is a layer-2 solution built on

Bitcoin Mining in the US: Main Challenges

Bitcoin mining in the United States has recently faced a range of challenges, from regulatory hurdles to community and environmental concerns. As a significant hub

Receive Our Insights

Subscribe to receive our publications in newsletter format — the best way to stay informed about crypto asset market trends and topics.

Share

Share  Tweet

Tweet  Post

Post